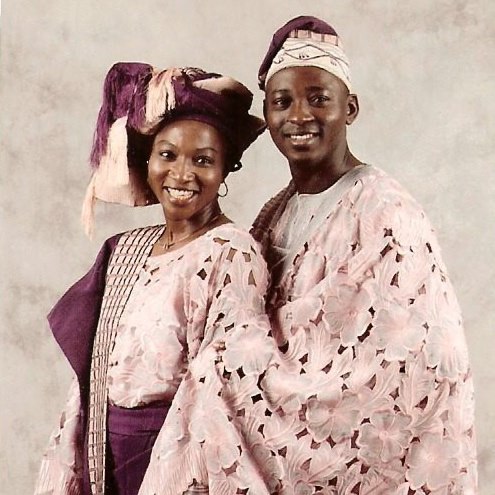

My last name, Oyerokun, which in Yoruba means “a royal person who has travelled overseas,” has proven to be somewhat prophetic. In the early 2000s, my parents moved from Nigeria to the United States to pursue their graduate education. Growing up, I appreciated my culture, but I was lacking a deep connection to my mother country. This could be explained by several factors: I have only been to Nigeria once as a toddler (see the photo of my mom and I above), I don’t speak much Yoruba, and I don’t know my family there well. However, since starting college, I have come to resonate with my Nigerian identity on a deeper level. I have rediscovered my Nigerian-ness and how I see my place in the world.

Back in the first grade, I mistakenly believed I was born in Nigeria, like my parents. While I embraced my nationality, I was embarrassed of my last name. People had a hard time pronouncing it, and it’s hard to be different, especially that young. I don’t think I had any Nigerian classmates until intermediate school, where the number of students in my grade quadrupled. There, I became more closely connected with kids I knew from our branch of the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG), a worldwide network of Nigerian churches. We frequently hung out after school functions. I could see how their families made up part of my support system- their parents would pick me up when mine were working late. Having to pronounce ‘Oh-YARE-oh-koon’ for other people no longer fazed me. It was just a fact. The things that made me different also brought me closer to others like me. Even though we had our petty fights, at the end of the day, I was one of them. Even though I might have taken it for granted, this community reinforced my identity in a formative way. When I created my Instagram account during my freshman year of high school, I put the Nigerian flag in my bio. I wanted people to know where Oyerokun came from.

Fast forward to now. I’m halfway through my time at the University of Pennsylvania and feel more Nigerian than ever. Black Penn played a major role. I was introduced to Black Penn during the Summer Institute for Africana Studies, where I earned credit for two mini courses. I remember how my mood brightened after a peer mentor and I learned we were both Yoruba. Perhaps this familiarity was part of the reason why I wasn’t that nervous to start college; I already knew I had a home here. I have found meaningful connections in my daily interactions, whether it’s catching up with people on the way to class or recapping my day. Last year, I took a step outside my comfort zone and became a resident advisor at Du Bois College House, which centers the experiences of the African diaspora. There, I strived to recreate the sense of community I experienced myself. Black Penn also has a strong African community, which puts on lively celebrations like the fake wedding party, which I look forward to every year. Sharing my cultural experiences with such diverse and interesting peers across the diaspora has brought me closer to home.

My academic experiences have also been invaluable. Freshman spring, I wrote my final research paper about Nigeria for Wrongful Convictions class, which exposed me to the brazen corruption in the police force. Questioning the legitimacy of the institutions that perpetuated these injustices sparked my curiosity about good governance and institutions. This confirmed my interest in political science. Sophomore fall, I took “Comparative Politics of Developing Areas”, where I explored Nigeria’s history of coups, tribalism, and transition to democracy. Fascinated, I called to ask my family members to share their stories. My father told me that he stopped voting after president-elect M.K.O. Abiola was arrested on the military’s orders. He no longer saw the point. Just this past semester, I made my final presentation in my Citizenship, Patriotism, and Identity seminar about the Indigenous People of Biafra movement, drawing connections between political theories and tribal tensions. These experiences have helped me better understand the context in which my parents grew up and how it shaped their worldview.

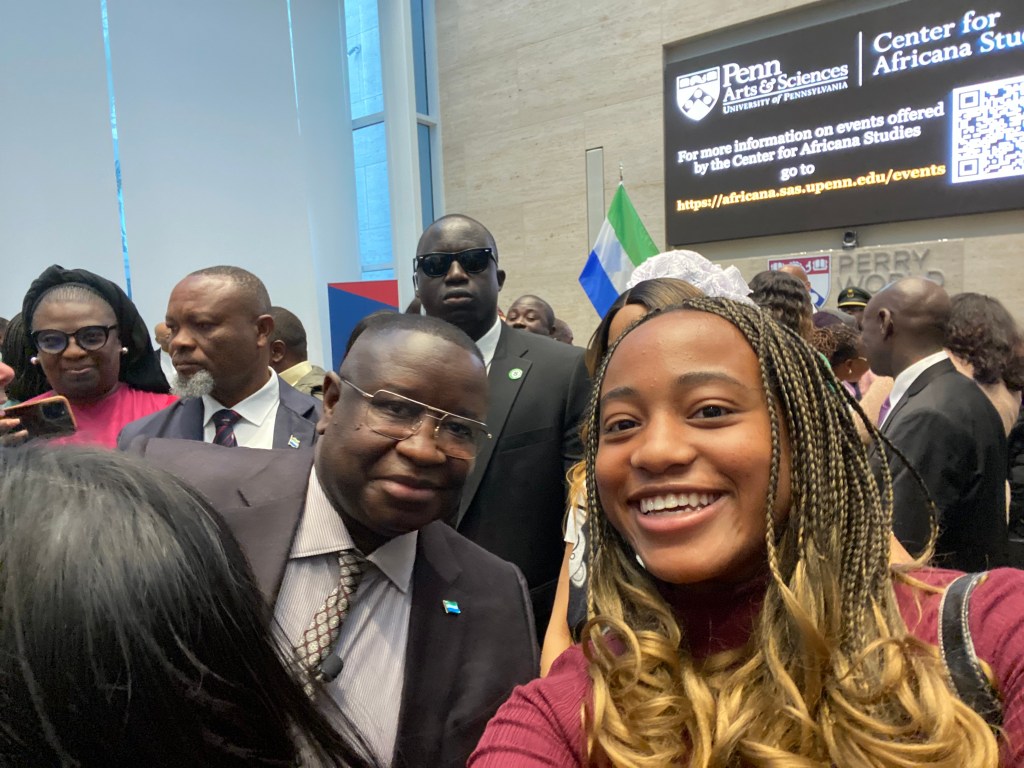

Since taking comparative politics and connecting with more students from other West African countries, my interest in Nigerian development and democracy has expanded to West Africa more generally. In March, I met the president of Sierra Leone, Julius Bio, when he came to Penn to give a talk about democracy and development. At the end of sophomore year, I met with Ghanaian and Senegalese professors to discuss their insights about politics in their homeland and the broader region. What would a better future look like?

I now see the pain in my parents’ success stories more clearly. In my dad’s words, they didn’t leave Nigeria; they “escaped.” Blatant corruption is the norm: People have even made headlines for blaming animals like snakes and monkeys for stolen funds. October first- independence day- means nothing to them. They have no hope. The exchange rate speaks for itself: 1530 naira to a dollar. For too many people, upward mobility is out of reach. Next summer, I hope to reconnect with my family there and engage in conversations with my generation about the future they want for themselves and the country. Do they share my parents’ valid cynicism? Or are they more optimistic about the potential for lasting change? I can’t wait to find out.